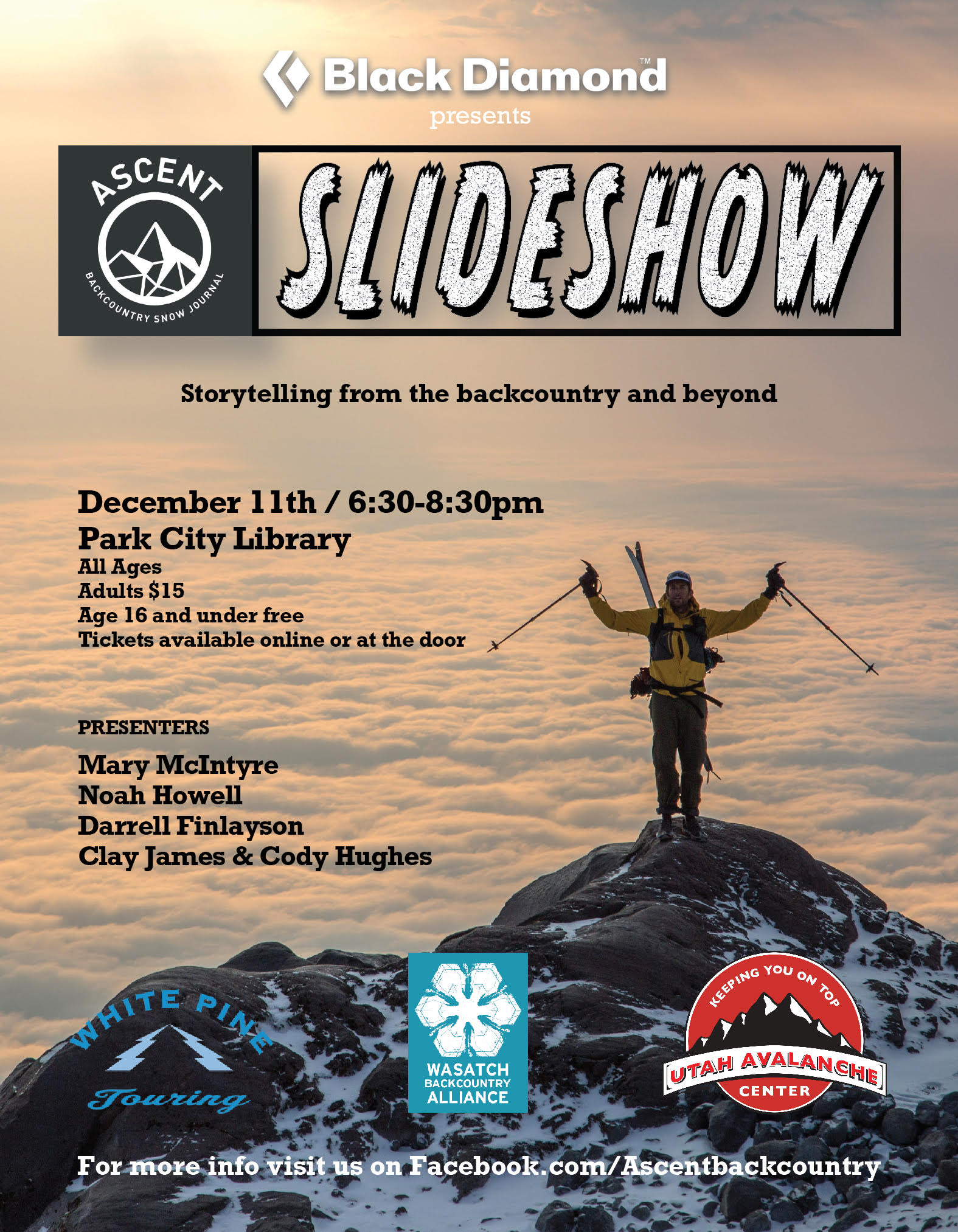

Steve Romeo self-arresting on 25 degree ice slope in New Zealand.

Mistakes Were Made, Lessons Were Learned.

In backcountry skiing, experience is something you gain from making lots of mistakes. There are endless books and videos on the sport, but nothing takes the place of learning from your own self-inflicted blunders. Assuming you could do it safely and survive; having Avalanche level 1 students get caught and buried on their first day of class would be infinitely illuminating. Likewise with taking a huge tomahawking whipper down an icy slope during a steep skiing clinic. After that, you’d then have everyone’s full attention. In many ways learning from your (or others) mistakes is far more educational than successes as it doesn’t set you up for a positive reinforcement loop such as thinking steep and deep slopes are safe just because you’ve skied so many of them.

An old climbing proverb states: “There are old climbers and there are bold climbers, but there are no old, bold climbers.” Boldness isn’t a necessity for most types of skiing, but there are plenty of other pitfalls along the way to becoming experienced in the backcountry. Some are serious, some are humorous, some are obscure and some are tragic. Here are a few of my favorite fails…

Try, Try Again

What you often don’t hear about notable ski descents is the number of aborted failures that it took to finally achieve them. The first time I tried to ski the Grand Teton we got completely lost and ended up doing an unintended first descent of a neighboring line which roughly fit the same description. We were in good company. After later describing this to Renny Jackson who wrote “The Climber’s Guide to the Teton Range,” he said “I had to stop giving new route credit to people who just got lost on existing routes.” Some mountain ranges, like the Tetons, are much more complicated than others and deserve extra trip preparation and detailed topos or maps.

The second time I tried skiing the Grand, I had excellent partners, but had a less than excellent tent. The tent worked well for backpacking, but was torn to shreds and scattered all over the mountain during a wind storm at night leaving me cocooned in flapping nylon and jagged broken poles. My more experienced partners slept well in their own tent and even asked “Was it windy last night?” I immediately bought a new expedition tent which turned out to be an unintended investment in my future as good gear makes tough camping much easier. By the time I finally skied off the summit of the Grand on my third attempt, I had learned a lot about ski mountaineering in general and the Tetons in particular, but that was just scraping the tip of the iceberg of mountain knowledge.

Booting up a chute in Iceland which would be filled with torrential avalanche debris about an hour later.

In 2005 we tried to ski Mt. Foraker in Alaska too early in the season before the warmer spring storms coated it with grippable snow. On a successful return trip in 2009 we almost erred on the other side by going so late that the Kahiltna glacier was a sagging mess of rotten snow bridges over gaping crevasses when we had to cross it one last time to get back to the landing strip.

Local Knowledge

Timing and luck are everything, although some descents defy even that. After aborting an attempt to ski the northwest ridge of Mt. Bona in the Wrangell Mountains of Alaska due to excessive crevasses and blue ice, I returned two years later to find… the exact same thing. I was surprised, but the locals, including bush pilot Paul Claus, weren’t. “That area is really cold, dry and doesn’t get much snow.” Oh well, now I know.

Ben Ditto shrieking with ecstasy after 40 minutes of hanging upside down over a huge crevasse by a single Dynafit toe piece in Alaska’s Wrangell Mountains.

On another trip, this time to the Canadian Rockies, I went to the effort of tracking down Doug Ward who had racked up a number of notable first descents in the area. He had great terrain information, but his timing advice; “The snowpack in April is transitional.” didn’t match my schedule. I was soon taught the folly of ignoring local advice as we broke trail through miles of flat, thigh-deep isothermal muck at a snail’s pace. With each hateful step the word “TRANSITIONAL” flashed through my mind in large red letters. The snow wasn’t light powder and it wasn’t firm corn. It was transitioning. We didn’t make it very far on that one.

Conversely, listening to and actually following local advice can deliver incredible skiing. Back when the Sierra range actually got snow and was having a banner year, I contacted John Moynier about skiing Split Mountain, and he redirected my attention to the Mendall Couloir in the Darwin range. I’d never even heard of this classic test piece, but the line was so filled in with perfectly bonded powder snow that the couloir almost skied itself – all you had to do was stand up and shake your butt to get down it. Another case was trying to ski Liberty Ridge on Mount Rainier with local ski guide Martin Volken. Instead of pressing on through gushing rain up Rainier, Martin suggested a trip to Mt. Buckner in the north Cascades, which turned out to be about as good as it gets. A flexible schedule and relaxed attitude goes a long ways.

The secret to success on big peaks is to throw lots of time at them. Sometimes you can luck out and ski them in a day or two, but more often than not you’ll have to wait out storms, hold out for a good weather window or let slopes stabilize for a few days. On a trip to Mt. Hunter in Alaska, we allotted two weeks for a run which ultimately took us 16 hours. Ticking off a big peak is incredibly satisfying, but if you don’t make it, the trip can feel like a failure. The ultimate scenario is to find a major objective surrounded by great backup skiing, but that combination seems hard to find as big peaks tend to be all or nothing. Another way to increase your odds of success is to pick an area with multiple skiing objectives instead of just one. Find a new zone on a topo map or Google Earth, fly in, set up a basecamp and have at it for a few weeks.

Partners in Crime

Almost every accident in the mountains involves some element of human error, which is often just a euphemism for “partners.” The ability for things to go sideways with the wrong partners can barely be overstated. Using trips as a way get sober or break up with a girlfriend is always a red flag, as is looking to buy recreational drugs as soon as the plane lands. Most of my partners have been well vetted, but not always.

Noah Howell kills time while waiting for conditions to improve by eating bacon straight from the bag.

On reaching the summit of Mt. Shasta during a springtime ski outing, Trish, a friend of a friend, announced she was completely spent and sat down. This didn’t seem too alarming as the clouds had been following us up the peak all day and it was now so socked in that people were randomly falling over from sheer vertigo as you couldn’t tell if you were standing still or moving. Trish eventually rallied, but as we were carefully picking our way down a ridgeline, she pitched off the backside and disappeared into the swirling white void. We only knew that she’d taken a long fall as we could hear her screaming all the way down, which finally ended in silence. Hmmm. After following her trail of terror down 1,500’ of a loaded avalanche slope, we found her at the bottom physically unharmed and announcing that this time she really, truly was spent. It was getting dark by now, but staying there for the night wasn’t an option, so we divided up her gear and booted back up through 1,500’ of thigh deep snow. Trish was far too shaken to ski, so we booted down the ridge to where our camp was, only to find that another barely known partner had decided to “help” us out by taking our tent and sleeping bags down with him earlier in the day. Now pitch black, the walking continued down through the aptly named “Bunny Flats” until we finally reached the parking lot well past midnight. In retrospect, skiing something serious like Mt. Shasta without even knowing your partner’s last name was probably not such a good idea.

In 2007, although I did know this person’s last name, I should have been warned when a few weeks before the trip he emailed to say that, although he was sorry he wasn’t in shape, he’d try to make up for it by taking the stairs instead of the elevator whenever possible. He was along as a friend-of-a-friend and didn’t take it too personally when our tours consisted of seeing him in the morning when we started out together and then again at the end of the day as we crossed paths skiing back to camp. The terrain we were in was mellow enough to justify solo skiing, but in steeper or more complicated mountains the disparity in physical conditioning would have been a trip wrecker.

Steep & Deep

It’s unfortunate that “steep” and “deep” rhyme so well, as they’ve became a marketing catch phrase for a potentially dangerous combination along the lines of “flame” and “game.” Getting burned by avalanches is not a fun pastime, but there have been a few humorous lessons learned along the way.

In my first and only season as a professional avalanche forecaster, I went out with my boss for a field day during a spell of high avalanche danger. On our first run we worked our way down a ridgeline observing classic avalanche danger warning signs like shooting cracks, natural releases, collapsing and easily triggered intentional slides. By the time we reached a mellow col the danger was blatantly obvious, but after both agreeing that we’d never seen this slope slide before, I dove in without first giving it a cautionary ski cut. My first impression was that I’d forgotten to buckle my boots as I had almost no ski control, but then I realized I was in a slide and a few moments later everything went dark as I was buried. Luckily my feet were still sticking out and although I later swore I was buried for a minute or more, my boss was able to pull me out after roughly 30 seconds. To add insult to stupidity, the slide broke on a 30 degree slope and ran on a 28 degree bed. I guess low angle slopes do slide.

Greg Hill topping out after 3,000’ of bullet-proof ice on Mt. Crosson on a failed attempt to climb and ski Mt. Foraker.

On another occasion, as I was approaching a cornice, I turned around and said to my partner “Have you seen that YouTube video of the guy who has the cornice break right under his feet?” A nano second later the entire cornice broke off, with my feet on the wrong side of it taking me for a 50 foot ride along with huge blocks of snow. This had a happy ending, and although I lost a GPS, I also gained an instant respect for how far back cornices can break, especially on windy ridgelines.

It’s a fine line between bravery and stupidity, but if you can live through your mistakes, laugh at them and learn from them, you’ll gain valuable experience. In retrospect, mistakes are always painfully obvious and easily avoidable, but when you are having fun and living in the moment, they are much harder to anticipate. Being able to see a dangerous situation developing is one thing, but knowing enough to take corrective action is an essential skill to skiing longevity. This is easier said than done. Once while a friend was nervously queuing up to jump off of a cliff, an encouraging bystander called out “What could possibly go wrong?” Taking three steps back and getting a running start at it, the skier charged the take off and flew into the air while screaming “EVERYTHING!” before perfectly sticking the landing. It was great.